No single piece of equipment is more synonymous with the medical profession than the stethoscope. I can vividly remember wearing my brand new Littmann stethoscope with pride on ward rounds as a medical student, desperately trying to discern diastolic murmurs and extra heart sounds with little success. Few people realise that if it wasn’t for the shyness of a young French doctor called Rene Laennec that this amazing piece of equipment may never have been invented.

Born in 1781, Rene Laennec was allegedly inspired to become a doctor due to his own childhood illnesses and the death of his mother from tuberculosis at an early age. He was a gifted scholar and studied medicine in Paris under several famous physicians including Guillaume Dupuytren and Jean-Nicolas Corvisat. Part of his training by Corvisat, who was a strong proponent of the use of percussion, was in the art of using sound as a diagnostic aid. He was also an accomplished flautist.

Early 19th Century Drawing of Rene Laennec

During the early 1800s, it was commonplace for doctors to listen to the heart by pressing their ear directly on a patients chest or back. In 1816 Laennec was presented with an overweight young woman complaining of heart problems. He felt uncomfortable with examining her in the traditional manner but he came up with a solution that would go on to change the practice of medicine forever. Laennec later described the incident the book De l’Auscultation Médiate, published in August 1819:

“In 1816, I was consulted by a young woman laboring under general symptoms of diseased heart, and in whose case percussion and the application of the hand were of little avail on account of the great degree of fatness. The other method just mentioned [direct auscultation] being rendered inadmissible by the age and sex of the patient, I happened to recollect a simple and well-known fact in acoustics, … the great distinctness with which we hear the scratch of a pin at one end of a piece of wood on applying our ear to the other. Immediately, on this suggestion, I rolled a quire of paper into a kind of cylinder and applied one end of it to the region of the heart and the other to my ear, and was not a little surprised and pleased to find that I could thereby perceive the action of the heart in a manner much more clear and distinct than I had ever been able to do by the immediate application of my ear.”

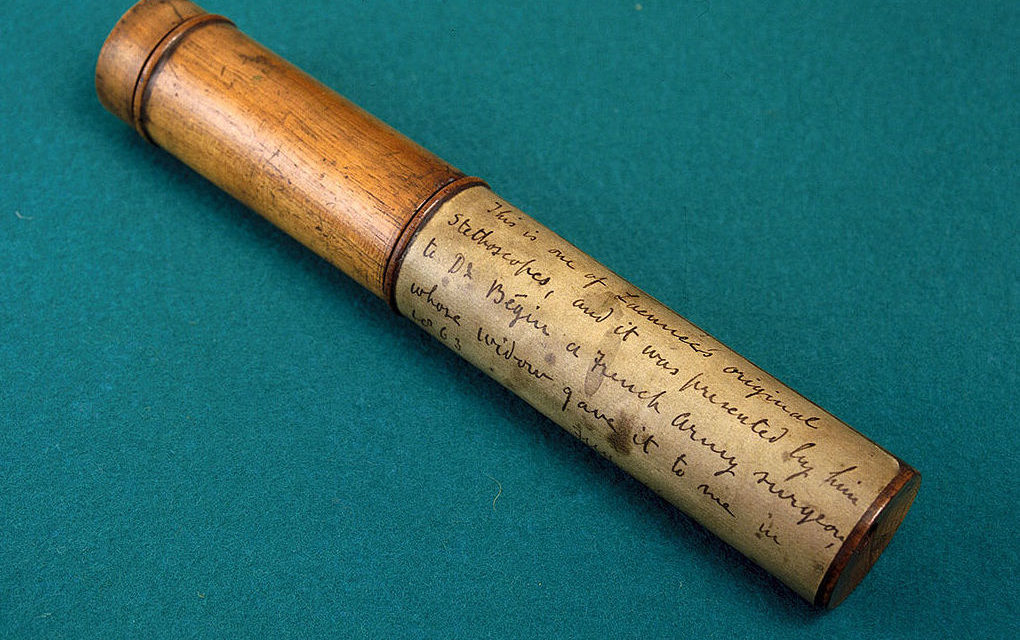

Laennec was so impressed with the results of his impromptu experiment that he went on to build a wooden version of it that could be carried around and used on patients during his day-to-day medical practice. His first instrument was a 25 cm by 2.5 cm hollow wooden cylinder, which he later refined to consist of three detachable parts. He called his creation the stethoscope from the Greek words ‘stethos’ for chest and ‘scopos’ for examination.

Picture on an early Laennec stethoscope sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of the Science Museum London CC BY-SA 2.0

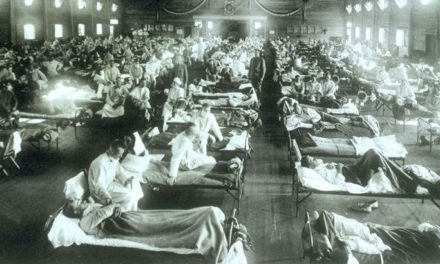

He presented his findings in a talk at the Académie de Médecine in 1819 and use of the stethoscope was rapidly adopted by physicians, initially across Europe and then later across the Atlantic in the US. Sadly Laennec died just a few years later in 1826 at the age of just 45. He died from tuberculosis, a disease which he had spent much of his career treating. Before his death, he called the invention of the stethoscope “the greatest legacy of my life”.

Laennec’s stethoscope was somewhat cumbersome, requiring the doctor to lean across the patient, and this led to a series of improvements over the years that followed. In 1840 the British physician Golding Bird created a flexible stethoscope that he called the snake ear trumpet. The Irish physician Arthur Leared further improved on this design, creating the first binaural stethoscope in 1851.

Golding Bird created the flexible ‘snake ear trumpet’ in 1840

The first commercially available stethoscope was patented later that year by the Cincinnati based doctor Nathan, but it proved too fragile to be used practically. The following year a New York-based doctor called George Camman successfully adapted this design to create a stethoscope that could successfully be produced and used by doctors across the world.

In the early 1960s, the Harvard professor David Littmann created his patented Littmann stethoscope, which was lighter than previous models and had improved acoustics. The Littmann stethoscope has remained the favoured choice of doctors ever since and just as I wore mine with pride on my medical student rounds in the 1990s, so do the latest batch of new enthusiastic trainee doctors today.

Excellent write up. thank you.

Dr Barton,

I was trying to remember the name of the doctor who invented the stethescope. Thank you for providing the answer. About thirty years ago, a Cardiologist in Florida wrote an article pertaining to the chambers and ventricles of the heart. As he looked at them through the film of the echocardiogram, he noticed that they formed the shape of the 21st letter of the Hebrew alphabet, known as the sheen. This letter is used for one of the names of God, Shaddai. Included in his article that this Jewish CARDIOLOGIST in Florida authored, he mentioned the first sounds of the heart heard by Dr Laennec heard as the heart chambers opened was the sound like “sshhhh” and when closing, it sounded like “dah”. Put together “shhhdah” was quite similar dinner sound to the name of God, Shaddai. In conclusion, our hearts have the shape of Gods Name, while every beat declares His Name. ShaddaiLet everything that has breath, praise the Lord”.

Had Rene Laennec been able to do immediate auscultation of the chest of a patient by placing his two ears simultaneously in contact with the patient, his first stethoscope for mediate auscultation would undoubtedly have been with two chest and two ear pieces.

Boghos L. Artinian MD