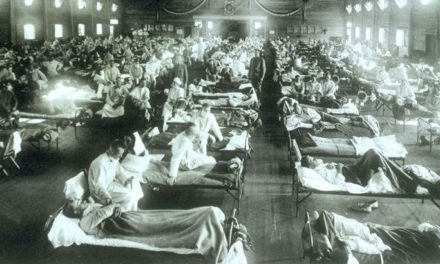

In August 1854, Soho in London was struck with a severe cholera outbreak. Cholera is a gastrointestinal infection caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae. It is still prevalent in areas with inadequate sanitation and poor food and water hygiene and remains a major global public health problem today.

The classic symptoms of cholera are sudden onset profuse, watery diarrhoea, and nausea and vomiting. Its effects are dramatic, and up to 20 litres of water can be lost per day. If not replaced, this heavy fluid loss rapidly leads to severe dehydration, circulatory collapse, and in many cases, death.

Thousands of residents in the Soho area of London fell ill as a consequence of this outbreak, and at least 600 people died. But as awful as this outbreak was, it is likely that many more would have died if not for the work of a local doctor living in the area, John Snow.

An adult cholera patient demonstrating signs of severe dehydration (Image courtesy of the CDC)

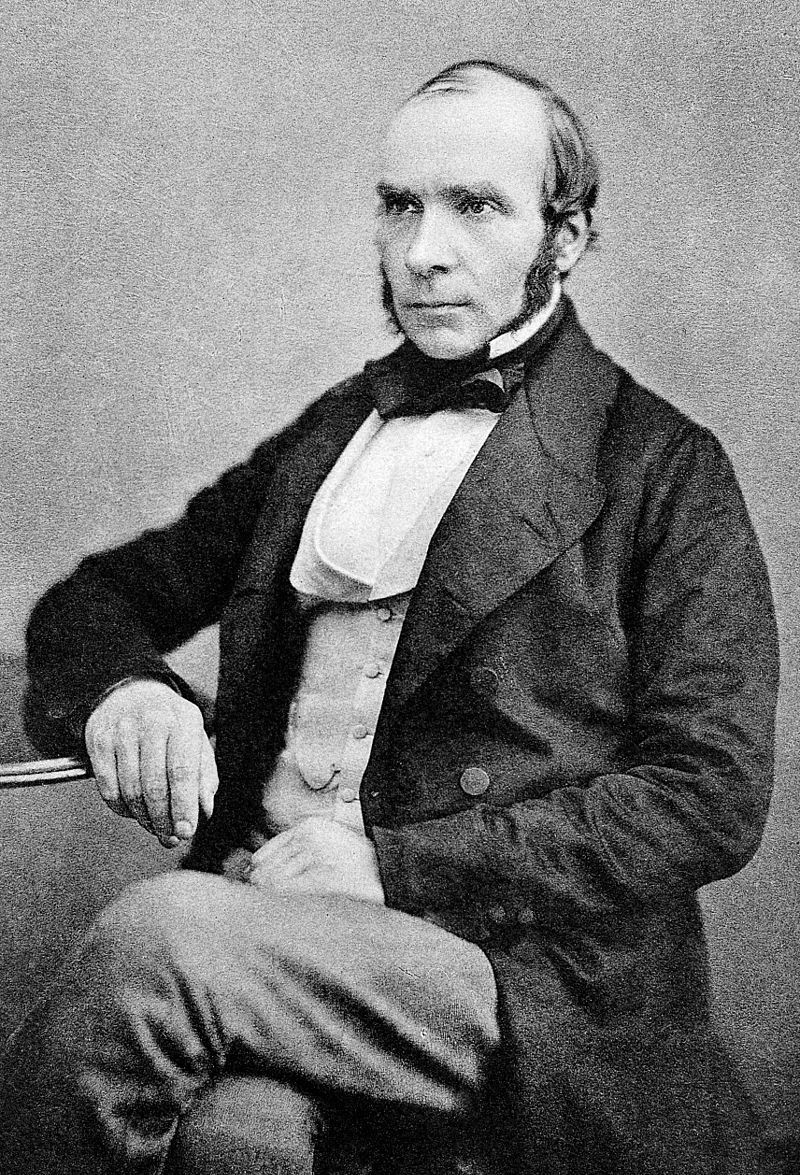

Who was John Snow?

John Snow was born on March 15th, 1813 in York, in the north of England. He was the first of nine children born to William and Frances Snow. Snow demonstrated an aptitude for science and mathematics as a child, and in 1827, at the tender age of just 14, he obtained a medical apprenticeship with William Hardcastle in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

It was in 1832, during this apprenticeship, that Snow first encountered a cholera epidemic, in Killingworth, a nearby mining village. He treated many victims of the disease during this outbreak and became very accustomed to its clinical presentation and how it seemed to spread.

The first case of cholera in England was reported a year earlier in 1831. At that time, it was thought that cholera was spread by ‘miasma’. Miasma theory held that disease was spread by a poisonous form of ‘bad air’ that was emitted from rotting organic matter. This theory was supported by several leading figures in public health at the time, including Edwin Chadwick and Florence Nightingale.

In 1837, Snow began working at Westminster Hospital, in London. He was admitted as a member of the Royal College of Surgeons in 1838, he graduated from the University of London in 1844, and was admitted to the Royal College of Physicians in 1850.

After completing his formal medical education, Snow set up his practice at 54 Firth Street in Soho, as a surgeon and general practitioner. It was here that he was based during the cholera outbreak in 1854.

Courtesy of Renato Sabbatini CC BY-SA 4.0

The Broad Street cholera outbreak

Snow was already sceptical of the miasma theory of disease, and he believed that sewage dumped into rivers and cesspools near town wells could contaminate water supplies and cause cholera outbreaks. As a doctor working in Soho, he started to investigate the 1854 outbreak immediately, in an attempt to prove his theory.

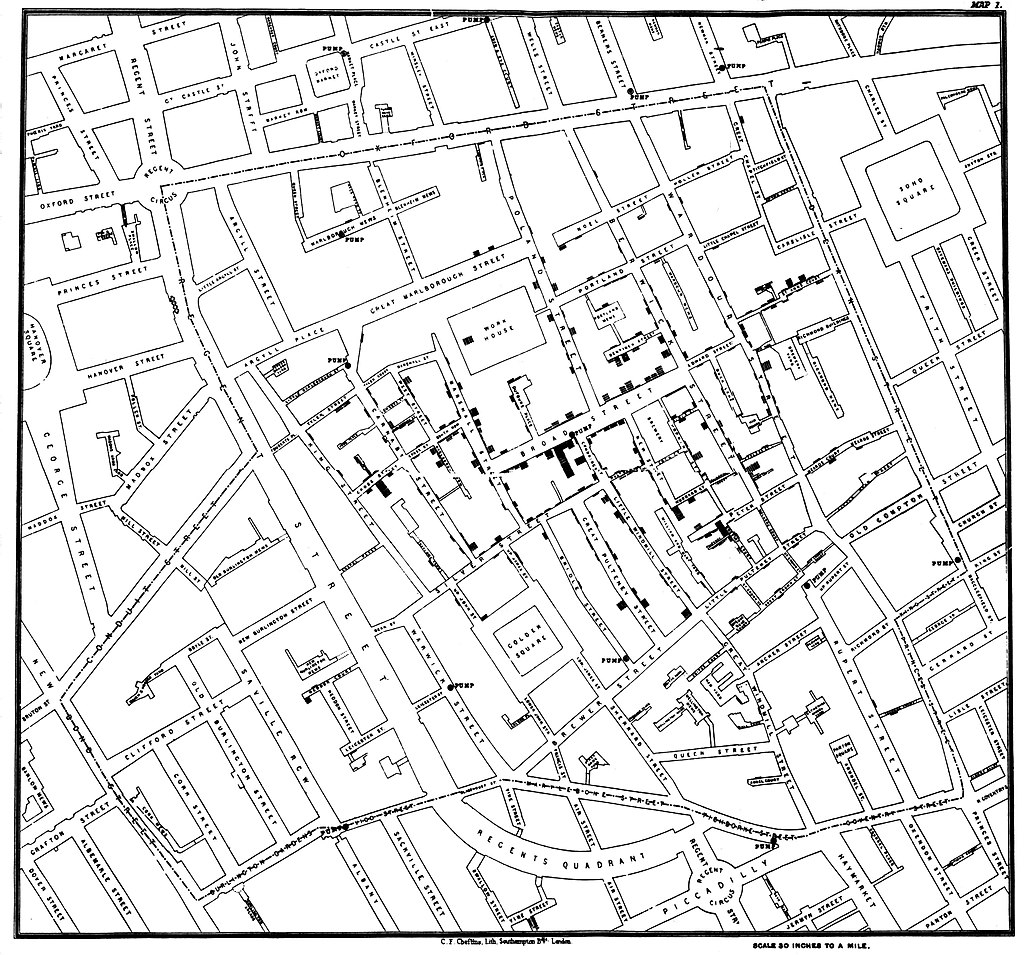

Snow began by talking to local residents and quickly started to suspect that the source if the outbreak was the public water pump on Broad Street. He used information from local Hospital and public records and specifically asked residents if they had drunk water from the pump. Using this information he went on to create a dot map to illustrate the cluster of cases around the pump. Snow wrote:

“Within 250 yards of the spot where Cambridge Street joins Broad Street there were upwards of 500 fatal attacks of cholera in 10 days… As soon as I became acquainted with the situation and extent of this irruption (sic) of cholera, I suspected some contamination of the water of the much-frequented street-pump in Broad Street.”

Original map by John Snow showing the clusters of cholera cases in the Broad Street outbreak, drawn and lithographed by Charles Cheffins

On the 7th September 1854, Snow took his findings to local officials and convinced them to take the handle off the pump, making it impossible to draw water from it. Shortly after this action, the outbreak came to an end, and the pump handle was promptly replaced.

Researchers later discovered that the public well from which the pump drew water was dug only a few feet from a cesspit. The cloth nappy of a baby, who had contracted cholera from another source, had been washed into this cesspit and was the point source of the outbreak.

The John Snow memorial and public house, on Broadwick Street (formerly Broad Street), Soho, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Renato Sabbatini CC BY-SA 2.0

Snow’s legacy

Shortly after the removal of the pump handle and the end of the outbreak Snow presented his views on cholera and its spread to the Medical Society of London. His views, however, were rejected by the medical establishment of the time. His ‘germ’ theory of disease did not start to become accepted until 1866, when William Farr, initially one of Snow’s chief opponents, realised the validity of the theory when investigating a new cholera outbreak in Bromley-by-Bow.

In 1883, the German physician, Robert Koch, isolated the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, finally discovering the cause of the disease. He determined that cholera is spread through unsanitary water or food supply sources, supporting Snow’s theory from 20 years earlier. His findings led to the changes in sanitation and water supply that finally ended the cholera epidemics in Europe and the United States that were occurring during the 19th century.

Snow sadly would never live to see his theories proven. He suffered a stroke while working at his practice on the 10th June 1858, and died six days later. He was only 45-years-old at the time of his death. He is now considered to a pioneer in the field public health and epidemiology, and he also did a great deal of notable work in the field of Anaesthetics, by testing the effects of ether and chloroform.

John Snow’s grave at Brompton Cemetery, London, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Edwardx CC BY-SA 2.5

Article image of cholera used on licence from Shutterstock

Wonderful historical review. It is good to remember how public health began.