Before the 1800s surgery was a risky business. In some London hospitals, the post-operative mortality rates were as high as 80%, and a mortality rate of 50% was considered acceptable. Operations were horrendous ordeals for the patients, with many dying on the table or shortly after from blood loss or post-operative shock. Those that were fortunate enough to survive the procedure then had to run the gauntlet of infection, and because of the limited understanding or how infection was spread at the time, the rates of sepsis were appallingly high.

All this would change, however, with the pioneering work of Joseph Lister, the man who is now widely acknowledged as the ‘Father of Antiseptic Surgery’.

The Early Life of Joseph Lister

Lister was born in West Ham, Essex, in 1827. He was the son of Joseph Jackson Lister, an amateur scientist who was influential in developing achromatic lenses for microscopes.

Lister was brought up in a strict Quaker home and attended Benjamin Abbot’s Isaac Brown Academy, a Quaker school in the Hertfordshire town of Hitchin. His parents took an active role in his education also, with his father tutoring him in the art of microscopy from an early age. He excelled in school and gained a place to study botany at University College, London, one of only a small number of institutions that accepted Quakers at that time.

Lister was awarded a degree in botany in 1847 and then registered as a medical student in 1848. He graduated with honours as a bachelor of medicine in 1852, and he became a house surgeon at University College Hospital the same year, where he would go on to obtain Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons.

One of his physiology tutors, Professor Sharpely, recommended that he go to Edinburgh to study under the renowned surgeon James Syme. Syme was widely acknowledged as the greatest surgical tutor of the time and was extremely influential on Lister.

In April 1856 Lister married Syme’s eldest daughter, Agnes, and a few months later in October, he was appointed surgeon to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. A few years later, at just 33 years of age, he was he was appointed Regius Professor of Surgery at the University of Glasgow.

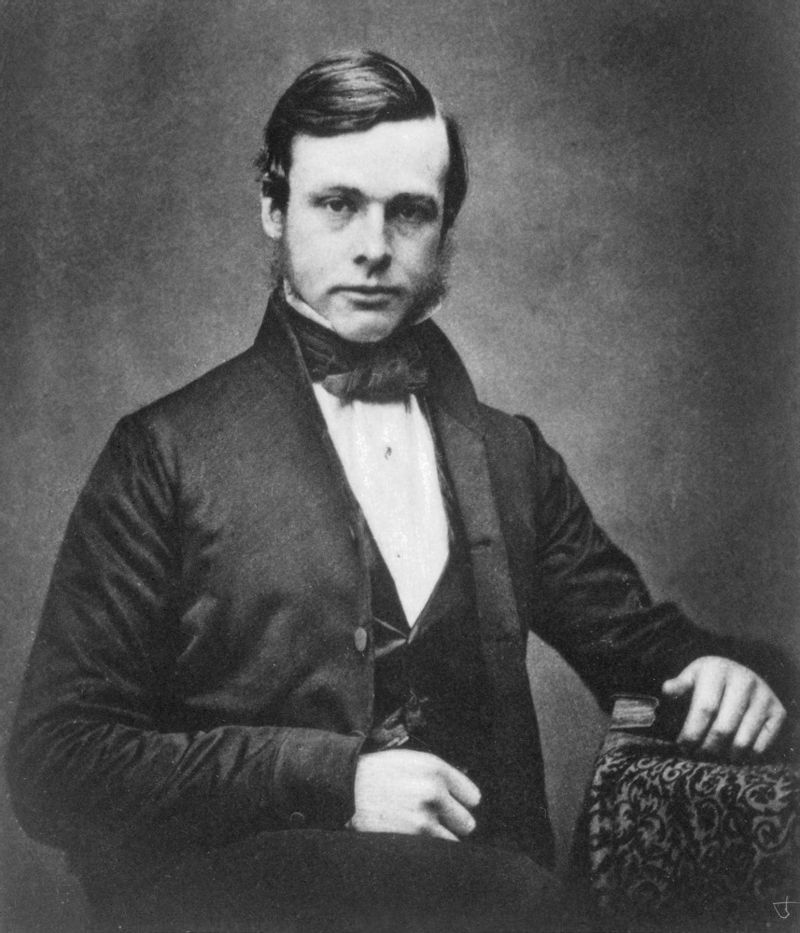

A portrait of Joseph Lister in 1855

Germ Theory of Disease

In the mid-1800s the germ theory of disease had not yet been established, and the miasma theory was still strongly supported. Miasma theory held that disease was spread by a poisonous form of ‘bad air’ that was emitted from rotting organic matter.

A representation of miasma theory by the artist Robert Seymour.

By the mid-1800s the germ theory of disease started to gain some traction, first through the largely ignored work of Semmelweis on puerperal infections, and later through the work of Pasteur and Koch.

While working at the University of Glasgow Lister became interested in a paper published by the French chemist, Louis Pasteur, which demonstrated food spoilage could occur in anaerobic conditions if micro-organisms were present. Lister had noted that between 45 and 50% of his amputation cases between 1861 and 1865 died from sepsis, and Pasteur’s work led him to believe that the same micro-organisms might be responsible for these infections.

The Birth of Antiseptic Surgery

In 1834 a German chemist, Freidlieb Ferdinand Runge, discovered a carbolic acid. Lister felt that this substance had potential as a disinfectant and he started to experiment with it on his patients. Initially, Lister used the carbolic acid to clean compound fracture wounds, and the results were quite remarkable. He described his findings in a report in the Lancet in 1867:

“Previous to its introduction, the two large wards in which most of my cases of accident and of operation are treated were amongst the unhealthiest in the whole of surgical division at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary, but since the antiseptic treatment has been brought into full operation, my wards have completely changed their character; so that during the last 9 months not a single instance of pyaemia, hospital gangrene or erysipelas has occurred in them.”

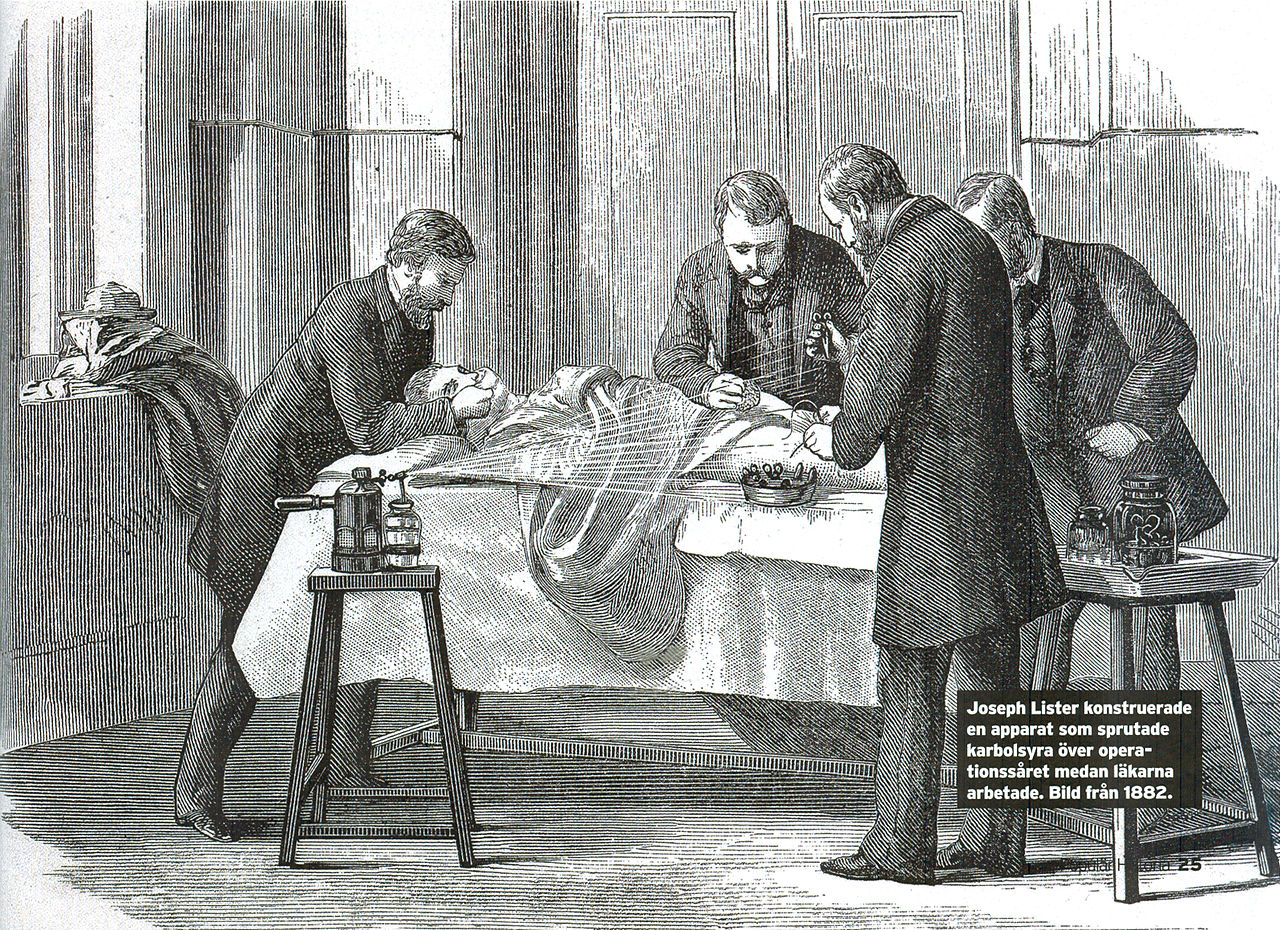

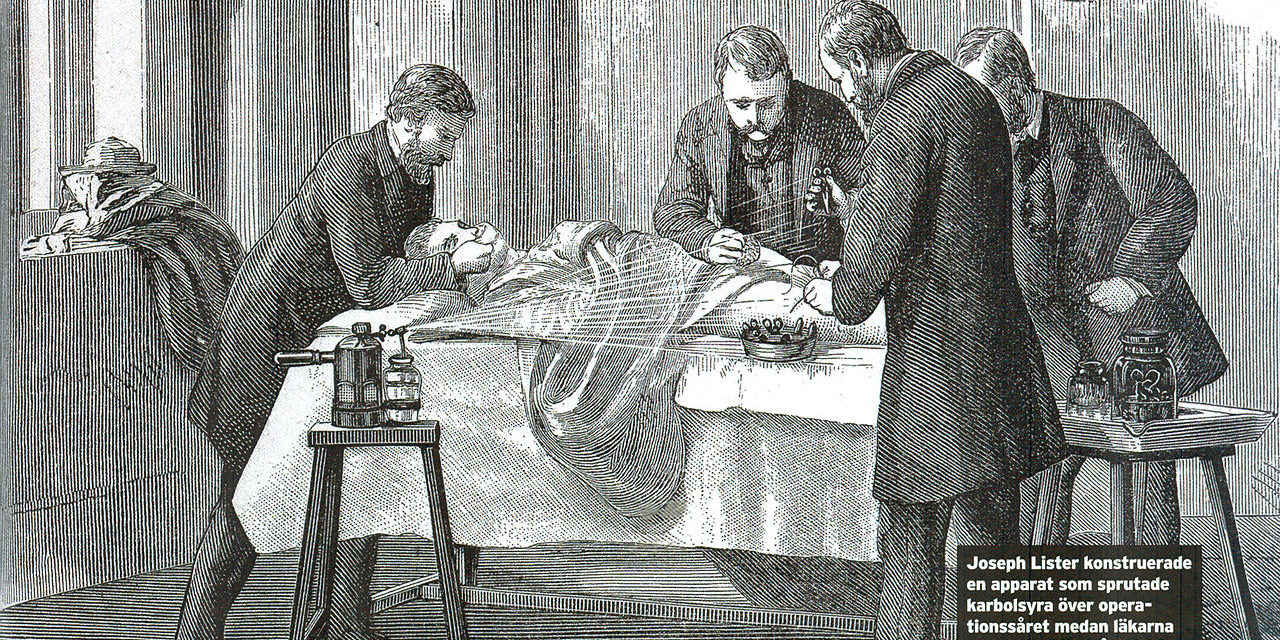

Spurred on by the success of these early experiments, Lister developed a machine that distributed a fine mist of carbolic acid into the operating theatre around the surgical site. He also instructed surgeons under his supervision to wear clean gloves and to wash their hands before and after operations with 5% carbolic acid solutions. The surgical instruments were also washed in the same solution. The combination of these antiseptic measures resulted in a dramatic fall in the death rate of Lister’s surgical patients from close to 50% to only 15% in 1870.

Despite this success, Lister’s antiseptic surgery techniques were greeted by harsh criticism early in his career and were widely rejected by his peers.

Lister spraying a surgical wound with carbolic acid.

Acceptance and the Spread of Antiseptic Technique

In 1869 Lister returned to Edinburgh as successor to his mentor James Syme. Gradually, over time, a few surgeons started to incorporate the use of carbolic acid and antiseptic techniques into their practice. One notable supporter was Marcus Beck, a consultant surgeon at University College Hospital, who not only used Lister’s antiseptic techniques with success but also included instruction on them in a major surgical textbook he wrote. It took 12 years for Lister’s techniques to gain widespread recognition though.

A group of surgeons in Munich emulating his practice achieved astonishing results in the mid-1870s, reducing their infection rates from 80% to almost zero. Ironically, it would be Lister’s English compatriots that would be the last to accept his work and incorporate his techniques into their practice, and it was only when he was appointed Professor of Surgery at Kings College Hospital London that they would finally follow suit. By 1879 antiseptic surgery techniques were being widely used all around the world.

Lister’s Legacy

Lister retired from practice in 1893 following the death of his wife Agnes and subsequently faded from the limelight. He would come out of retirement briefly though, when King Edward VII developed appendicitis in August 1902.

Appendicectomy was still a high-risk procedure at that time, despite the progress that had made, and he was eagerly consulted by the surgical team responsible for the King’s care. Lister advised them on the latest antiseptic techniques of the day, and after painstakingly following his advice, the surgery went well, and the King survived. Edward VII later told Lister, “I know that if it had not been for you and your work, I wouldn’t be sitting here today”.

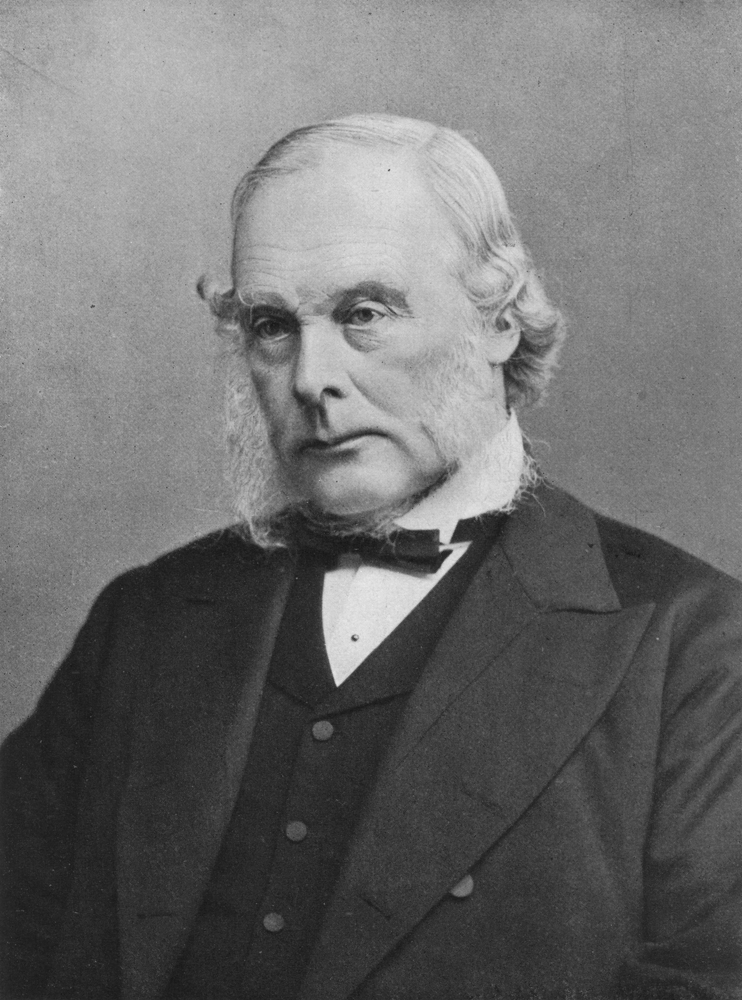

A portrait of Joseph Lister in 1902.

Lister died on February 10th 1912 at his country home in Walmer, Kent, aged 84. Unlike many other early proponents of the germ theory of disease, such as Ignaz Semmelweiz, Lister was fortunate enough to see his ideas accepted while he was still alive. His application of germ theory and antiseptic techniques have laid the foundation for modern surgical practice and created a powerful legacy that has lasted many generations after his passing.

Recent Comments