The Middle Ages are renowned for being a turbulent and difficult period of history. War, famine and disease occurred throughout the period and one of the most devastating pandemics in history, the Black Death, occurred in the mid 14th century.

The Black Death was not the only disease to wreak havoc in this period though, and another disease, now known as ‘Sweating Sickness’, or ‘The English Sweate’ claimed thousands of lives in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The first outbreak

In the summer of 1485, at the start of the reign of Henry VII, a previously unseen disease started to spread across England. Some have suggested that it was brought to England by French mercenaries in Henry Tudor’s army but this is by no means certain and there are no reports of it affecting the Tudor army.

Henry Tudor arrived in London shortly after the Battle of Bosworth Field on the 28th August 1485 and the disease was first reported there less than three weeks later on the 19th September 1485. The disease then proceeded to run rampant in London, killing thousands and striking panic in the population.

Sweating Sickness first appeared in England shortly after the Battle of Bosworth Field.

One of the most terrifying features of the disease was the speed with which it could kill. There were numerous reports of people dropping dead in the street suddenly. Thomas Forrestier, a French physician living in London at the time, wrote of the disease:

“We saw two prestys standing togeder and speaking togeder, and we saw both of them dye sodenly. Also in die—proximi we se the wyf of a taylour taken and sodenly dyed. Another yonge man walking by the street fell down sodenly.“

‘A great sweating and stinking’

The disease spread quickly and began suddenly, the afflicted suffering violent cold shivers, dizziness, thirst, headaches, joint pains, and a sense of apprehension. Some also reported that sufferers had a malodorous smell and appeared red and flushed. There appeared to be an initial ‘cold stage’ that lasted a few hours, followed by a ‘hot sweating stage’. One attack did not appear to offer immunity and some people suffered several bouts before dying.

The following description by Thomas Forrestier paints a vivid picture of what the disease must have been like:

“And this sickness cometh with a grete swetyng and stynkyng, with rednesse of the face and of all the body, and a contynual thurst, with a grete hete and hedache because of the fumes and venoms.”

It seems that the most dangerous stage of the disease was the first few hours and that those who survived the first 24 hours would go on to make a full recovery.

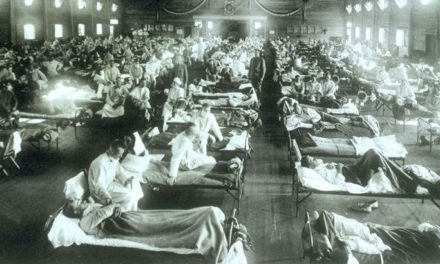

Subsequent outbreaks

The 1485 outbreak lasted until late October that year and then disappeared for several years. There were reports of smaller outbreaks at periodic intervals but it was not until 1507 that a large outbreak occurred again. In 1517, a third and much more severe epidemic occurred that also spread across the channel and struck Calais, where it remained mostly confined to the English population. In 1528, the disease reached epidemic proportions again, this time it spread into parts of Europe including Hamburg, Switzerland, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, although none of these was as severely affected as England. The last major outbreak of the disease occurred in England in 1551 and after this, it disappeared completely and has never been seen again.

Scourge of the English upper classes

One of the most perplexing aspects of the disease was its predilection for the English upper classes, especially rich young men. Unlike many other medieval diseases, it seemed to spare the very young and the very old. It became known as ‘The English Sweate’ because it did not spread to Scotland, Ireland and Wales. It also seemed to affect foreigners living in England less severely.

It was most commonly seen in rural areas but also severely affected the nobility living in London and the student populations of Oxford and Cambridge. In later outbreaks, Cardinal Wolsey would contract the disease twice and recover on both occasions but it claimed the lives of a large number of his household on both occasions.

Cardinal Wolsey is thought to have contracted the disease twice, in 1517 and in 1528.

It would also affect the court of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn is said to have contracted and survived the disease. Chronicler Edward Hall commented on how it affected the Kings court and nobility in London:

“Suddenly there came a plague of sickness called the sweating sickness that turned all his [the King’s] purpose. This malody was so cruel that it killed some within two houres, some merry at dinner and dedde at supper. Many died in the Kinges courte. The Lorde Clinton, the Lorde Gray of Wilton, and many knightes, gentleman and officiers.”

Many Englishmen unsuccessfully tried to escape the disease by fleeing to Ireland, Scotland, and France only to die there. John Caius wrote in his 1552 publication ‘A Boke or Counseill Against the Disease Commonly Called the Sweate or Sweating Sicknesse’ that “It followed Englishmen like a shadow”.

Several hundred years later in 1881, Dr Arthur Bordier submitted a paper to the Anthropology Society of Paris entitled ‘On the special susceptibility of the fair-haired races of Europe for contracting sweating Sickness’. In the paper, he presented an interesting, but unproven theory that Sweating Sickness did not solely affect Englishmen but instead had a tendency to infect those descended from the Anglo-Saxon and spared those descended from the Celts.

What was the cause of the Sweating Sickness?

There have been several hypotheses over the years as to the exact cause of the Sweating Sickness. Some have suggested that it was actually influenza, whilst others have suggested it was caused by anthrax or relapsing Fever.

One of the most compelling cases is that it was caused by hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. In 1993, an outbreak of this disease struck the Navajo people in New Mexico. This outbreak, known as the Four Corners outbreak after the region in which it was located, bore many resemblances to the Sweating sickness, prompting investigators to suggest it as a potential cause.

Like Sweating Sickness, hantavirus is characterised by a sudden onset of a fever, joint pains, headache. This is followed by shortness of breath and rapidly evolving pulmonary oedema that usually requires mechanical ventilation and has a mortality rate of 35-40% despite modern medical intervention.

The mystery lives on…

Despite the various theories as to why it behaved in such a strange manner, mainly affecting English nobility, and to the exact cause of the Sweating Sickness, we are still none the wiser. It may be that we never unravel the mysteries of this disease and that it will never be seen again.

oh my could one now suggest the virus only spread in the circle of those that mixed and how similar to what we are seeing in this day but without any obvious class distinction due to the mingling of the gentry with the rest of us.

Sorry, I hope you understood my intention I did not mean to imply that any social class is to blame for the spread of disease.