This story, set in 1880s post Civil War America, particularly appealed to me due to my love of anatomy. The two main players in this unusual tale are very different individuals indeed. The first, Harriet Cole, was an African-American woman who worked as a cleaning lady at Hahnemann Medical College (now the Drexel University College of Medicine) in Philadelphia. The second, Dr Rufus B. Weaver, was the Medical College’s leading Professor of Anatomy. Together this odd couple would be responsible for the creation of one of the world’s most captivating and astonishing medical specimens.

Harriet’s demise and generous donation

In 1888, at just 35 years of age, Harriet Cole died from tuberculosis. Having worked for some time at the Medical College, she agreed to leave her body to Dr Weaver and requested that it be used for the benefit of science and medicine. It is very doubtful that Harriet knew what Dr Weaver would do with her body though, and the extraordinary legacy that she would leave behind for future generations.

Dr Weaver had travelled through Europe a few years earlier and had witnessed several intricate partial dissections of the nervous system. No one had successfully managed to dissect the nervous system in its entirety though, and shortly after Harriet’s death, he set out to rectify this.

Dr Weaver’s amazing achievement

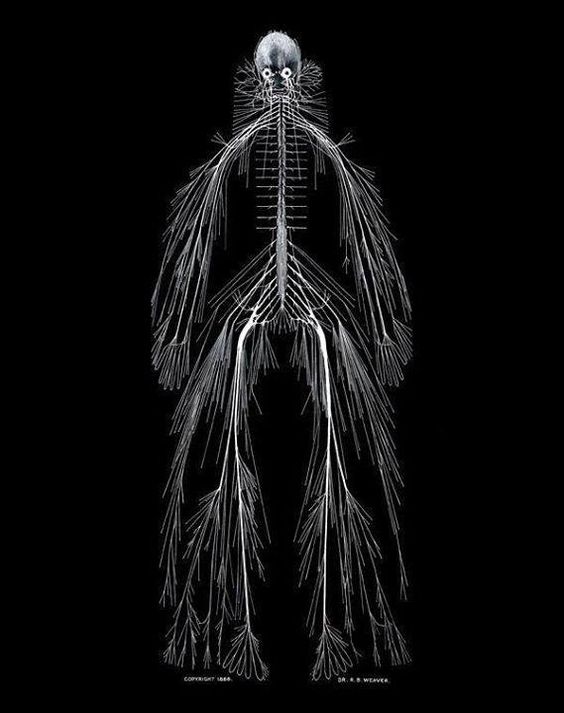

In March 1888, Dr Weaver set to work, and over the course of the next five months he would painstakingly dissect out every nerve. His attention to detail was incredible. The base of the skull was chipped away piece-by-piece, maintaining the integrity of the dura mater, the cranial nerves were separated out using fine needles, and even the eyes were left attached. Initially, each nerve was wrapped in moist gauze for protection, before being covered in a lead-based paint for long-term preservation. The only nerves that he was unable to dissect out successfully were the tiny strand-like filaments of the intercostal nerves that sit between the ribs. Thousands of pins were then used to suspend the fully dissected nervous system from a blackboard. Dr Weaver affectionately referred to his achievement as simply “Harriet”.

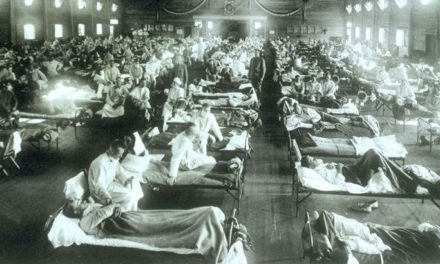

The fully dissected nervous system of Harriet Cole in all its glory.

Legend has it that when Dr Weaver informed an English doctor about Harriet, he replied that: “It is impossible, there is no such thing in all this United Kingdom, and if it had been possible it would have been done by someone.”Dr Weaver modestly responded to this statement by saying: “So it has, by someone in the States.” Another physician,Dr Alfred Heath, later described Harriet as “a marvel of patience and skill in dissection, the likes of which have never been seen before.”

Harriet’s legacy

Harriet served as an educational tool at the College initially, but she was destined for greater things. In 1893, she was taken to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where she received an exhibition medal and the blue-ribbon Premium Scientific Award.

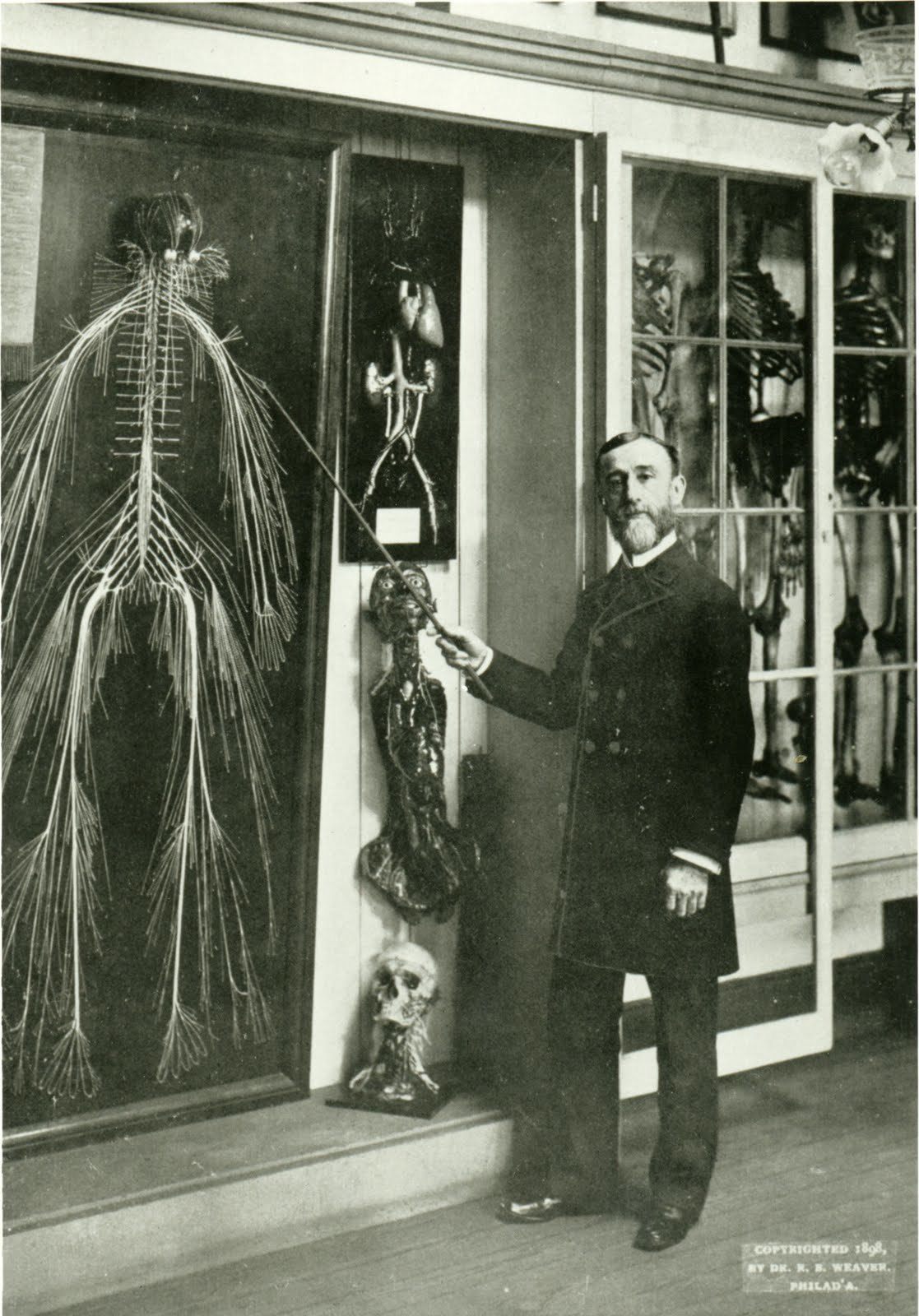

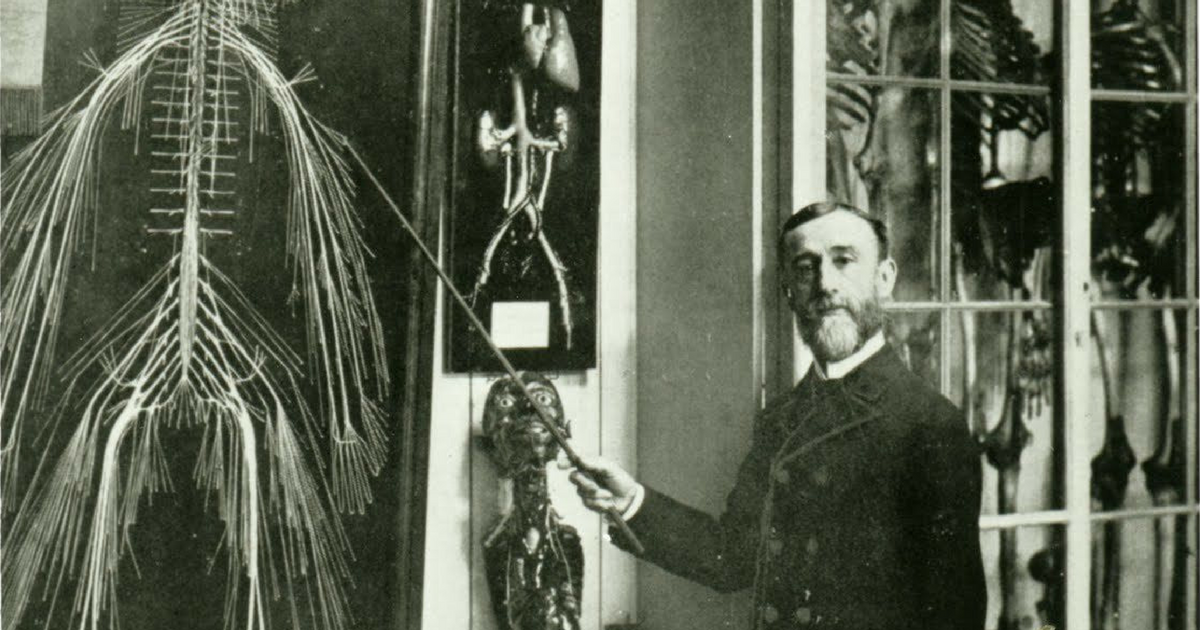

Dr Rufus B. Weaver proudly displaying “Harriet”

Images of the incredible dissection have featured in hundreds of anatomical and medical textbooks and laboratories around the World and Drexel University apparently still receives photo requests to this day. Although “Harriet” is no longer used as an official teaching tool at the University, she still stands proudly within a glass case welcoming students at the entrance of the University bookshop.

Recent Comments