In the summer of 2016, a 10-year-old Russian boy cut himself skinning a marmot whilst hunting with his grandfather in the remote Kosh-Agach region in the Atlai Mountains. A few days later he developed a fever and a flu-like illness and was taken to a local hospital. He had contracted bubonic plague.

His case caused panic and hit the international news. Everyone he came into contact with was quarantined and thousands of emergency vaccines were administered. Fortunately, his case was isolated and fears of an outbreak proved to be unfounded.

The last major outbreak of bubonic plague in Russia occurred almost 250 years earlier in 1770 and the outcome was very different indeed. It was a devastating epidemic that claimed the lives of as many as 100,000 people.

The Russo-Turkish war

In 1770 the Russo-Turkish war was well underway. The conflict had started in 1768 and was contested between the Ottoman Empire and the Eastern Orthodox coalition, that was led by the Russian Empire. The majority of the war was fought in the Balkans and Caucasus, where the plague was endemic in some areas.

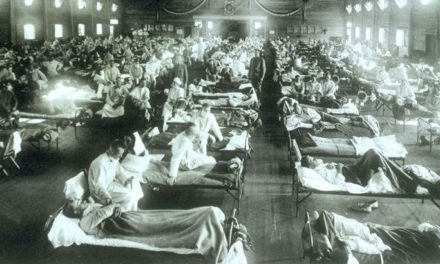

In January 1770 some Russian troops stationed in Maldova started to develop feverish illness and swollen lymph nodes. Gustav Orreus, A Russian-Finnish surgeon stationed with the troops, recognized the symptoms and signs immediately and identified the illness as being bubonic plague, an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Yersinia Pestis. An outbreak developed and 1,500 troops subsequently contracted the plague by August of 1770, of these only 300 survived.

Yersinia Pestis is a particularly nasty bacterium that can infect both animals and humans. It uses rats and other rodents as a reservoir species. Fleas then act as a vector species, acquiring Yersinia Pestis whilst feeding on the infected rodent and the bacteria is then passed to humans via a fleabite. The classic sign of bubonic plague are buboes, horribly swollen lymph nodes. These most commonly appear in the inguinal nodes, situated in the groin region because most fleabites occur on the legs. Those infected will first experience fevers, chills and muscle pains before developing septicaemia or pneumonic plague. Death can occur in less than 2 weeks.

The classic ‘buboes’ of bubonic plague.

The plague reaches Moscow

Medical quarantine checkpoints had been set up years earlier by Peter the Great, and these had proved to be very efficient at preventing the plague from entering Russia during peacetime. The effectiveness of these checkpoints fell apart during wartime though, and in the Christmas of 1770, it finally spread all the way to Moscow.

Dr Shafonskiy, the chief physician at Moscow General Hospital, identified a case of the bubonic plague and promptly reported it to a German physician Dr Rinder, who was in charge of the public health of the city. Unfortunately, Dr Rinder didn’t trust Shafonskiy’s judgement and ignored his report.

Government officials chose to listen to Rinder and also ignored Shaifonskiy. Unfortunately, by the time that it became obvious to everyone that this was an outbreak of bubonic plague, it was too late to stop the spread with the traditionally employed measures and it had started to take hold. In February 1771 the plague broke out at a textile mill in the city and workers from the mill started to spread the plague around the city. By the spring of 1771, a major epidemic was in full effect. In June 1771 Dr Rinder himself contracted the plague from a patient and died a few days later.

The Plague Riot

The government responded to the epidemic by setting up hospitals and quarantines around the city. The rich started to flee to the neighbouring countryside, but the city was shut down to the poor, who were not allowed to leave.

Some of the measures instituted by the government were interpreted as being heavy-handed by the city’s populace. Contaminated property was destroyed without compensation, public baths were closed and many felt that the government had trapped them inside the city on purpose.

1930s Watercolour of the Plague Riot by E. Lissner

The plague peaked in September 1771, killing over 1000 people every day. Fear and anger were widespread, and protests against the measures taken started to occur. In mid-September, Archbishop Ambrosius attempted to prevent citizens from gathering at the Icon of the Virgin Mary in central Moscow as a quarantine measure. This lit the torch paper of the Plague Riot and on September 15th, 1771 huge crowds of angry citizens descended upon the Red square, invaded the Kremlin and destroyed the Archbishop’s residence. The following day the situation worsened and the Archbishop was murdered by the rioters. The riot was eventually suppressed by the military, but not until 3 days and a huge amount of destruction had occurred.

The murder of Archbishop Ambrosius by Charles Michel Geoffrey (1845)

Grigory Orlov takes control

Following the riot, Empress Catherine dispatched Count Grigory Orlov to take control of Moscow. Orlov was an interesting figure and was a trusted favourite of Empress Catherine. He had led the coup that overthrew her husband Peter III and installed Catherine as Empress a decade earlier and was also rumoured to have been her lover.

Orlov arrived in Moscow on September 26th, 1771 with four regiments of troops and immediately called an emergency council with the local doctors.

He went on to do a good job, gaining the trust of the people and changing public opinion about the government’s emergency measures. With Moscow’s medical commission fully engaged and the support of the people, the quarantine methods employed started to take effect. Through October and November, the number of new cases started to slow down and on November 15th Empress Catherine declared that the epidemic was officially over.

There would be further deaths in the early part of the following year, but with effective quarantine measures in plac,e only 330 deaths were reported in January 1772.

The consequences of the Russian plague

The plague would have long-lasting effects upon Moscow. The epidemic would ultimately reshape the map of Moscow as new cemeteries were established outside the city in an attempt to both combat the epidemic and deal with the astonishing death toll. Taxes and military conscription quotas would be markedly reduced in many provinces and it the effects would alter the course of the Russo-Turkish war.

The estimated total death toll from the epidemic lies somewhere in the region of 100 thousand people, which was an astonishing one-third of the population of the city of that time.

Recent Comments